Comics & comics analysis

Comics |

|

Comics use several sign-languages at the same time in their images that are also accompanied by words. These signs can only get decoded without larger variations in meaning (connotations) if they are established with precisely one denoted meaning. As images they make possible the description of states and stages in a view images, while one would need many words to describe these. But the associations possible are extremely wide with images, so it is never guaranteed that images are decoded like intended by the encoder. The use of pictograms in various contexts shows the lack of limitations to the use of images as signs: While the meaning of words is defined in dictionaries, it is impossible to fix the meaning of images like that, as not only the elements of each image but also its borders, the perspective chosen etc. are transporting possible meanings. "Possible" is essential here, all these factors do not have to carry meaning in each individual case. The difference between a narration in written texts and in image/text-combinations is a fixture in storytelling.

|

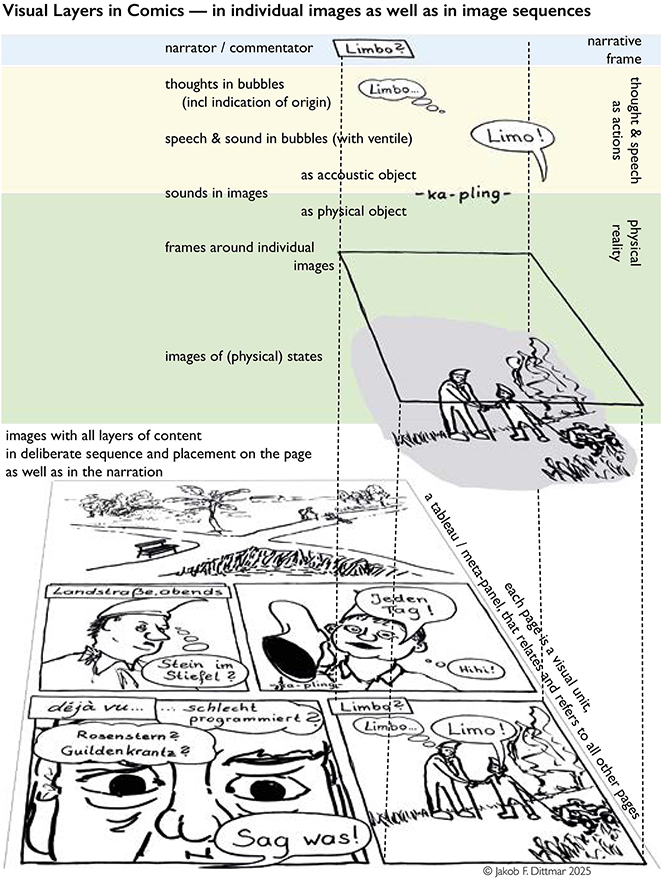

All the visual elements in a comic can be imagined to be placed on separate layers that in their combination constitute the comic - the image on the right is visualising this concept (described in more detail in my book "Comic Analyse", see below). It explains how comics are built, and it helps when analysing and describing particular comics and their narrative and stylistic strategies: Frames organise the pace and structure of a image-sequence. In this, frames around each image can be visible or invisible - in that case the next image still arts where the previous one ends, allowing for ambiguities in constructing and also in reading theses sequences. The content of frames can be images that in their turn can contain images and texts that represent speech, thoughts, or sounds. Also, frames can contain the narrator's explicit voice. It is implicit in the point of view of the images and in what elements of the story are shown to the readers etc, but as we have the different layers, the narrator's position or perspective / strategy in the text-boxes can be completely contradictory to the perspective shown in the images. Some comics do not show thoughts, use no thought-bubbles at all. Others do not use text in speech-bubbles but represent speech as pictograms or images. Each of these choices is distinct for understanding the narrator's strategy, so to say, it also is crucial visually, as it has consequences for what is shown in pictures and how. Text can be more abstract, while images tend to be more concrete. Consequences of placement of content on distinct layers in eithe rimages or text are massive for what can be negotiated in a comic - and how. To illustrate the principle: While the words "a dog" can remain a general reference to a typical dog, any drawing of a dog tends to show a particular type or even an individual dog. To write "democracy" takes one word, to draw the concept takes much thought and space on the page. In comics, the images not only work individually but also in combination: Each new page is a new experience of the images in combination and individually alike: the whole page works as a meta-panel (or hypercadre) that consists of all its individual images and combination of their designs (in accordance with definitions in film, one can call this effect mise-en-page). Decisions about the number of images and their placing and style are crucial for the storytelling style of each comic, as the designs of pages and images in reference to each other's dominating graphic elements gives the author control over the design of each full page. For example, sometimes, large signs dominate the entire page - and are composed from elements in individual images and only assemble to the large sign in synchronicity - when seeing the entire page. |

|

Different options and restrictions apply for printed comics and for web-comics and again digitally presented comics, most obviously in regards to the page design as a whole. Narrative strategies depend on the medium, obviously, and while the options and necessities of page-turning can be simulated on-screen, the pacing of web-comics tends to be quite different from printed comics. Duly, the experience of reading is different not only because of the medium used but also because of the way, content is arranged for the development of the story. The underlying principle has been defined by Thierry Groensteen in his seminal "Système de la bande dessinée": each image has to be placed somewhere specific (it is in it's place), and that placement relates to the comic's narrative (the space / espace of that comic) as well as to all other elements in their distinct places in a comic. When we analyse a comic, we need to understand how elements of it are used to introduce and develop the narration, how the different elements of the comic on their layers are used to express information and create an athmosphere, and style. The same applies when we plan a comic, we need to decide how to use the elements the comic is to be constructed from, page by page, to create exactly the story that we want to tell. But remember in this context that we may be superprecise in our planning and execution of the entire comic, but still, the readers make sense of what they see - and they can of course read something else into it, maybe because of some symbol and its meaning for them / in their (sub-)culture or because of changing contexts etc.

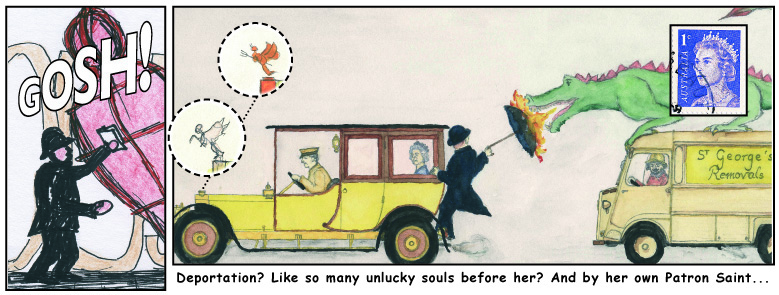

Here is a link to a digital comic, infinite canvas-style: Done with Beckett, in which the text level creates variation between a smaller number of repetitive images. The individual images as well as the sequences of images refer to other contexts than the texts. At the same time, images and texts relate to each other to tell their story.

Content on both layers invite to follow up on references in images or texts, but it is up to the reader to ddo this - or not. Dependent on given education, interests the same comic narraties differently, the difference is created knowingly or un-knowingly by the reader, not by the comic! Of course, reading is an active process: each reader creates their own understanding of the matter read: in comics this are the images, their elements, sequences of images, and the texts and their elements as well as their design. It remains true that communications after they are published (not just texts and images, but also films etc.) develop meanings that cannot be controlled by their authors/creators as they are received or set in all kinds of different contexts (this is what Roland Barthes called "the death of the author").

Information-ComicsInto which literary field we place documentary, journalistic and other non-fictional comics or comics that tell of natural science or other scientific or other knowledge is not settled, yet. Within this area are comics that are reflective, or essayistic, almost - and there are a lot of examples with an outright didactical aim, but to call these "educational comics" seems to be too unspecific - from drama theory we can borrow insights on the matter: Bert Brecht aimed his plays to be epic and didactic, they intent to invite the adience to reflect critically on the story told. His aim was to break the audience's immersion and compassion with the figures on stage to enhance reflection and learning. Information-comics are similar in their approach, while their narrative forms get more and more differentiated. Genres within the field of information-comics are fluid and some even blend fictional and non-fictional strands of narration. It remains to be seen how comics theory deals with these - in practice they are developing a splendid width and depth of options. There are (amongst others) maintenance comics (e.g. by Will Eisner for the US-Army, amongst others in "The Preventive Maintenance Monthly") mounting instructions in comics form (e.g. ikea-manuals), as well as documentary (starting with Joe Sacco) and scientific reflective (e.g. John G. Swogger's "Ceramics, Polity, and Comics") The difference between information-comics and other can be summarised like this: Comics are in our general understanding not produced and distributed to explain a technical artefact or how to assemble or service it. They usually narrate independently of attached artefacts with an entertaining purpose. When looking at public health-instructions, manuals or mounting instructions we find sequential graphic narrations, non-fictional comics quite simply, providing no thrilling plots, but stringent information and with a narrative purpose, e.g. on how to assemble your flat-pack furniture or how to wash your hands to reduce spreading some illness for example. Also, there are comics that try to teach in a non-fictional way on history, natural science issues or the Geneve Convention etc. Here is a link to Yalla Yalla, an experimental comic published by Calice Magazine, reflecting on the working conditions of parcel delivery workers in Berlin. It is strong on aspects, places, details of places, but in how far it is documentary and how far it is essayistic depends on the reader, seemingly. Depending on your cultural knowledge, the comic shown next to this text is depicting the lighting of a blue candle or it alludes to specific memory practice - here the lighting of a blue candle to remember and think of your friends and co-players in the Schlaraffic role-playing game. With or without the specific cultural information the comic makes sense and is readable, of course. But it gains different meanings according to its readers' cultural knowledge / frames. While non-fictional comics depend extremely on reference to realities outside of the comic's narrative, this is of course also true for fictional comics and the references contained within these (their point in the words of Keith Jonstone (s. his: Impro for Storytellers. Chapter 5. London: Faber&Faber 1999). |

|

Defining Comics

The currently best definition of comics is Ann Miller's (bande dessinée is French for comics) (in: Reading Bande Dessinée. Bristol: Intellect, 2007; p. 75):

"bande dessinée produces meaning out of images which are in a sequential relationship, and which co-exist with each other spatially, with or without text." This definition refines Scot McCloud's definition and is much clearer on text in comics.

Where comics start and picture books as illustrated texts end remains matter for debate. Where the images provide crucial information that is not given by the text, the images stop being mere illustrations, obviously. If images tell the story mostly and texts provide additional information to contextualise the images in specific ways, we are safely on comics-territory.

There are no one-image comics. One image can show and detail a situation, a moment, a state of things. It can be in whatever style or genre, maybe a cartoon, or a painting that can hint at a before and after to the moment it describes. An image can be allegorical and much more, but it is not a sequence and as such can not tell a story really (s. Detlef Hoffmann (ed.): Erzählende Bilder. Oldenburg: Isensee 1998 for more details). There is no before-after-sequence for example. But an image can contain a sequence of states or stages that show a movement or action, and in that case it enters comics-territory as these can illustrate the passing of time, the consequences of actions, alternative states of things, etc. But strictly speaking it contains several images, maybe without visible frames, that are superimposed or inserted into the one background image. If you want to be restrictive with definitions, you can call these image-composites images with comics-narrational elements. Where they end and real comics start, has to be discussed for each individual case as they can differ a lot. As soon as we have at least two images that together tell a story, we should have a comic. There remain reservations as an agreement needs to be reached on what constitutes a story as well as if and how close to each other the images need to be placed.

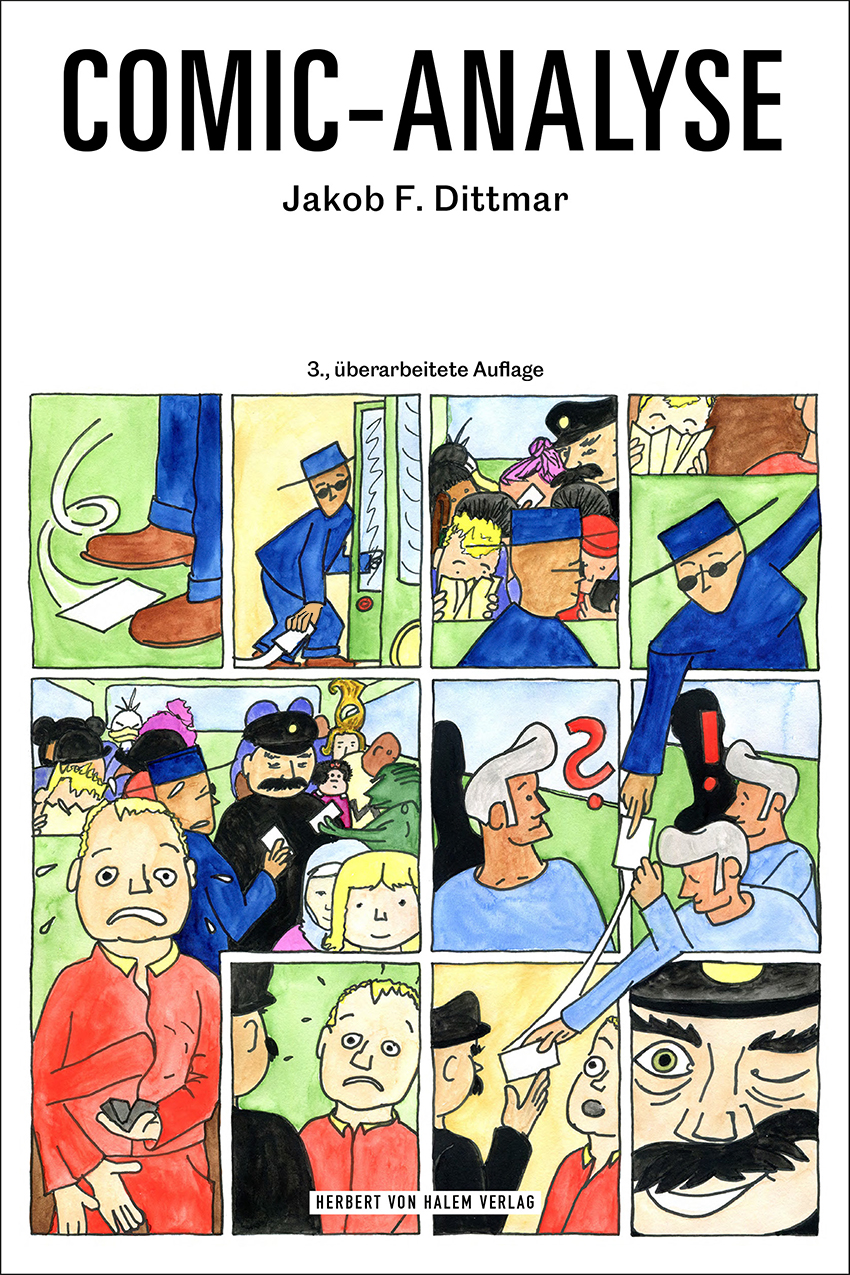

book: Comic-Analyse (in German)Announcement: The new and revised 3rd edition is to be published in April 2025. Comics analysis, as the title translates quite un-originally, develops a systematic for the analysis of all kinds of comics and other forms of picture stories, traditional European comics as well as Asian manga or even mounting instructions and maintenance manuals. My focus is not on any specific school or analytical approach, but rather looks into the material and how things are narrated, how images and texts are placed and form sequences. While the different theories and views applied in analysis absolutely have their merits (how else can we discuss what things might mean to us?), we need to look into the material itself first and describe it in detail before we put it into wider contexts. My "Comic-Analyse" simply provides the basics for describing comics material in detail.

Jakob F. Dittmar: Comic-Analyse. |

|

"Teaching comics-drawing over the internet - despite everything?" Forthcoming in: Krantz, Gunnar, Tina-Marie Whitman, Magnus Nilsson (eds.): Forthcoming anthology on Scandinavian Comics Research. DeGruyter, 2024/25.

"German Comic Art, Intergenerational Memory and Everyday Objects." (with Anders Høg Hansen). In: European Comic Art Vol 17/2, 2024; 49-82.

"defining forms or types (not genres): one-panel comics are a contradiction in terms" in: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 26:2, Winter 2024.

"Defining the Graphic Novel" in: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 24:1, Spring/Summer 2022; 608-622.

"Review of Johannes C.P. Schmid, Frames and Framing in Documentary Comics" in: European Comic Art, Vol. 15:2, 2022.

"Belonging in Auto|Biographical Comics: Narratives of Exile in the German Heimat" (with Ofer Ashkenazi). In: Nima Naghibi & Candida Rifkind, Eleanor Ty (eds.): Migration, Exile, and Diaspora in Graphic Life Narratives. Special Issue of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies. Vol. 35, 2; 331-357. London: Taylor&Francis.

"Narrative Strategies - African Types and Stereotypes in Comics" and the German interpretation of the English text:

"Erzählstrategien - Afrikanische Typen und Stereotypen in Comics" in: Corinne Lüthy, Reto Ulrich, Antonio Uribe (Hrsg./eds.): Kaboom! Von Stereotypen und Superheroes - Afrikanische Comics und Comics zu Afrika; Kaboom! Of Stereotypes and Superheroes - African Comics and Comics on Africa. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2020; 28-46.

"Comics as Historiography" (with Ofer Ashkenazi). In: Schmidt, Johannes and Laura Schlichting (eds.): Graphic Realities. ImageText 11:1, September 2019.

"Blind readers and comics - reflecting on comics' storytelling from a different perspective" in: Ian Hague et al. (eds.): Comics Forum. 4 August 2019.

"Negotiating Documentation in Comics" (by Ofer Ashkenazi and me). In: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 20:1, Spring/Summer 2018; 587-597.

"Abstraction and non-sequitur." In: Aarnoud Rommens, Pablo Turnes, Erwin Dejasse, Björn-Olav Dozo (Eds.): Abstraction and Comics. Brüssel: La 5e Couche (5c), 2019.

"Experiments in Comics Storytelling" in: Studies in Comics 6.1, 2015: Proceedings of the fifth annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference; 157-165.

"Sequential Images, the Page, and Narrative Structures" in: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 17:2, Autumn 2015; 561-571.

"Experiments in Digital Comics: Somewhere between comics and multimedia storytelling" in: Ian Hague (ed.): Comics Forum. March 13, 2015.

"Spirou – över 70 år av figurdesign" (in Swedish) in bild & bubbla nr. 201/2014; 98-101.

"Comics for the Blind and for the Seeing" in: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 16:1, Spring 2014; 477-86.

"Comics" (in German) in Jens Schröter (Hg.): Handbuch Medienwissenschaft. Stuttgart: J.B.Metzler; 258-261.

"Die Vermittlung von Zusammenhängen und Handlungsfolgen mit Hilfe beweglicher Elemente" (in German) in Urs Hangartner, Felix Keller und Dorothea Oechslin (Hrsg): Wissen durch Bilder. Sachcomics als Medien von Bildung und Information. Bielefeld: Transcript; 311-326.

"Comics and History: Myth-making in Nazi-references" in: International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 15:1, Spring 2013; 270–286.

"Digital Comics" in: Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art (SJoCA), Winter 2012; 82–91.

"Grenzüberschreitungen: Technikdokumentation und drei-dimensionale Bilder in fiktionalen Comics" (in German) in: Thomas Becker (Hg.): Comic: Intermedialität und Legitimität eines popkulturellen Mediums. Bochum: Bachmann Verlag 2011; 147-158.

"Comic und Geschichtsbewußtsein - Mythisierung im Gegensatz zur Historisierung" (in German)

in: Klaus Farin, Ralf Palandt (Hrsg.): Rechtsextremismus, Rassismus und Antisemitismus in Comics. Berlin: Archiv der Jugendkulturen 2011; 419-427.

Research paper "Comic" (in German) in: Historisches Wörterbuch der Rhetorik (HWRh).

Tübingen: Max Niemeyer 2011; 169-185.

"Jaki bodzie komiks cyfrewy?" ("Digital Comics" in Polish, translated by Michal Blazejczyk)

in: Zeszyty Komiksowe Nr. 10, pazdziernik 2010.

"Comics and History: Myth-making versus Historisation" (in Hebrew, translated by Ofer Ashkenazi)

in: Slil: On-Line Journal for History, Film and Television Winter-Issue 2010.

Comic-Analyse. (book in German)

Konstanz: UVK 2008 / 2011 now available at Herbert von Halem Verlag, Cologne.